The episode of WTF Happened to This Movie? covering Videodrome was Written by Jake Dee, Narrated by Matthew Plale, Edited by Diane Baldwin, Produced by Chris Bumbray and Ben Cantler, and Executive Produced by Berge Garabedian.

Have you ever considered how a movie becomes a bona fide cult classic? While many factors play a role, the phenomenon usually begins with a high-quality product that fails to resonate among the masses during its initial release due to ungraspable material ahead of its time, yet through its own undeniable merits, finds its passionate fanbase that grows over time and allows the film to become far more popular after the fact than it was in the present tense. In the case of David Cronenberg’s sci-fi body horror opus Videodrome, the film has overcome its notorious box-office failure to ascend as one of the most revered movies of Cronenberg’s illustrious career.

As Videodrome approaches its 40th birthday in February 2023, it’s worth breaking down what inspired the film, how it was made, and what production problems forced Cronenberg to alter his creative process, including the inventive ingenuity of the low-tech, DIY practical and video FX work and stunning make-up by the legendary Rick Baker, and ultimately, what doomed the film’s initial theatrical run and what led to its subsequent cult following over the next four decades. Sound good? Strap the f*ck in, and Long Live the New Flesh…it’s time to figure out WTF Happened to Videodrome ahead!

According to Cronenberg in the Criterion DVD audio commentary, the filmmaker drew inspiration for Videodrome from his childhood in Toronto, Canada, where he would illegally intercept American TV signals from Buffalo, New York, while staying up late at night after his local Canadian stations ended their broadcast. Cronenberg was terrified of witnessing content on pirated American channels he was not meant to see, including disturbing imagery that was not geared for mainstream public consumption. This spark of an idea ignited Cronenberg’s torrid imagination, telling Tim Lucas in Cinefantastique:

“I’ve always been interested in dark things and other people’s fascinations with dark things. Plus, the idea of people locking themselves in a room and turning a key on a television set so that they can watch something extremely dark, and by doing that, allowing themselves to explore their fascinations.”

Cronenberg also adapted the provocative themes of hyper-violence blended with lurid sexuality from his treatment for Network of Blood in the 1970s, a movie idea that also featured a protagonist that worked for a low-budget independent TV company that would ultimately evolve into the character of Max Renn in Videodrome. According to Cronenberg per Cinefantastique, the initial idea for the underground TV station was to explore “A private television network subscribed to by strange, wealthy people who were willing to pay to see bizarre things.”

Once the premise was locked, the plan was to tell the story from the protagonist’s first-person perspective, highlighting the dichotomy between how insane the character looks in the eyes of the public and how he himself perceives the altered states of reality happening inside his own mind. Cronenberg also incorporated elements from Network of Blood in the 1977 TV episode of the Canadian TV program Peep Show, entitled “The Victim,” giving the filmmaker an architectural blueprint that proved invaluable when it came time to write the screenplay for Videodrome. In a sly bit of social commentary, Cronenberg named the CIVIC TV station in the film after the real-life Canadian station CityTV, which was known for airing lurid pornographic material and ultra-violent movies during midnight broadcasts. During the film, one of Renn’s partners is named Moses, which is a bald reference to CityTV’s founder, Moses Znaimer.

Thanks to the financial success of his film Scanners in 1981, Cronenberg was able to secure funding for Videodrome much easier than he did earlier in his career on Shivers and Rabid. According to Cinefantastique, the success of Scanners allowed Cronenberg to obtain a production budget of $5.5 million from the Canadian Film Board and draw interest from various producers, studios, and above and below-the-line talent. Believe it or not, Cronenberg turned down the chance to helm Return of the Jedi to make Videodrome instead, citing his lack of interest in directing material produced by other filmmakers as the chief reason why (per Entertainment Weekly). While Cronenberg would have been an odd choice to oversee a Star Wars movie in the first place, his steadfast willingness to stick to his own creative sensibility only makes the filmmaker more respectable.

After declining to direct Return of the Jedi, Cronenberg reunited with producer Pierre David after collaborating on The Brood and Scanners and pitched him two different ideas, one of which was Videodrome (per Cronenberg on Cronenberg).

The first draft of Videodrome was penned in January 1981. As often the case with Cronenberg’s writing process, the initial draft featured wildly outlandish sequences that had to be excised in order to make the material more palatable for wide audiences. In the scripting phase, Cronenberg eventually axed a physiological element of Max Renn that would have featured an explosive grenade in place of his chopped-off flesh gun during a hallucination. The original draft of Videodrome also included Renn and Nicki melting into an object after sharing a kiss, which in turn melted a nearby witness. There were also five additional characters dying of cancer, like Barry Convex, who was modeled after American televangelist and convicted fraudster Jim Orson Bakker. Furthermore, the character of Professor Brian O’Blivion was based on famed scholar Marshall McLuhan, whom Cronenberg studied under at the University of Toronto. McLuhan coined the phrases “hot” and “cool” media in relation to the TV screen and its content, a thematic fulcrum for Cronenberg to spin his creative wheels around and sinisterly subvert in the film.

Another key scene that was omitted from the screenplay right before it was scheduled to be filmed included a hallucinatory reverie in which Renn’s TV rises out of a bathtub after displaying a harrowing image. The production went through painstaking efforts to achieve the sequence, including placing Woods in the bathtub and filling it up with clear non-conductive liquid. However, at $25 per quart, the process proved to be too expensive to employ. In the end, the SFX team waterproofed the interior of the TV monitor using layers of insulation, which worked like a charm after testing the method in a swimming pool. Despite the TV floating to the surface due to the large vacuum fixed inside the picture tube, the effect was nixed at the last moment.

Per Cronenberg on Cronenberg, the director was certain that his original draft would be roundly rebuked by the independent company Filmplan International due to the extreme violence and sleazy sexuality. Much to Cronenberg’s surprise, the script was approved despite Cronenberg’s longtime producer Claude Heroux joking that the film was destined to receive a triple-X rating.

With the script in shootable shape by the summer of 1981, casting on Videodrome began in earnest. Per Fantastique, producers suggested casting James Woods for the lead role of Max Renn, persistently following up on their failed attempt to cast the actor in a movie called Models a year prior. Because Woods was such a fan of Rabid and Scanners, he agreed to meet with Cronenberg in Beverly Hills to discuss the part. Per the DVD commentary, Cronenberg appreciated how articulate Woods’ line delivery was and according to Cinefantastique, Woods reciprocated the sentiment for Cronenberg’s strange style and for being a “good conversationalist” who exuded a lot of power.”

As for the casting of Debbie Harry, aka Blondie, for the role of Nicki Brand, it was producer Pierre David that suggested the pop-rocker for the role. Once Cronenberg studied Harry’s performance in the 1980 movie Union City in repeat viewings, he agreed to audition her for the part in Toronto. Harry credits Woods for assisting her with plenty of helpful tips while making the movie, something she relied on, having never played such a large speaking part in a movie before. Ironically enough, Blondie goes full redhead in the film, subverting her own pop image in lockstep with Cronenberg’s own sense of anti-mainstream rebellion.

Principal photography on Videodrome commenced in Toronto on October 19, 1981, and lasted until the early hours of December 24th. As a non-negotiable stipulation for being funded by the Canadian government, production had to be completed before the end of the calendar year and included a hard cut-off date, forcing Cronenberg to begin filming without a completed shooting script and with very little preparation time. While he did have the original script he thought would be rejected in tow, it served more as a guiding prototype while making the movie that would be pared down as time went on. While production had until December 31st to use the funds provided by the Canadian government, Cronenberg aimed to complete the film by Christmas Eve so that the cast and crew could enjoy the holidays with their families.

According to Criterion, the first week of the 2-month film shoot was dedicated to recording the video monitor insert shots of Brian O’Blivion’s bloviating TV monologues and the softcore pornographic simulations Samurai Dreams and Apollo & Dionysus. The camera used to film the video monitor sequences was a Hitachi SK-91 with Samurai Dreams filmed without any audio recorded at a Global TV studio rental space in Toronto. The sequence took half a day to complete and lasted 5 minutes longer than what appears in the final cut of the film (per Cinefantastique).

Despite disliking the flat, 2D TV format and feeling very uncomfortable filming violent sex scenes, cinematographer Mark Irwin stayed on board throughout the production. According to Cinefantastique, Irwin was much more comfortable filming with typical movie cameras than low fi videotapes and felt creatively hamstrung by the entire crew being able to see his lighting and camera setups on the monitors rather than having the privacy of blocking and arranging shots as he would on most movie sets.

One of the best decisions Cronenberg made during production was hiring Oscar-winning make-up FX legend Rick Baker to handle the film’s unique aesthetic. According to Screen Rant, Baker retained many of his twentysomething crewmates (whose average age was 23 years old) from American Werewolf in London, the first film in history to win an Academy Award for Best Special Make-Up, to work on Videodrome. As such, it’s time to dive into the nitty-gritty of how Baker, Cronenberg, and Special FX supervisor Michael Lennick achieved some of the sickest, surrealist, and most nightmarish moments that continue to withstand the test of time and haunt the memories of cinephiles everywhere.

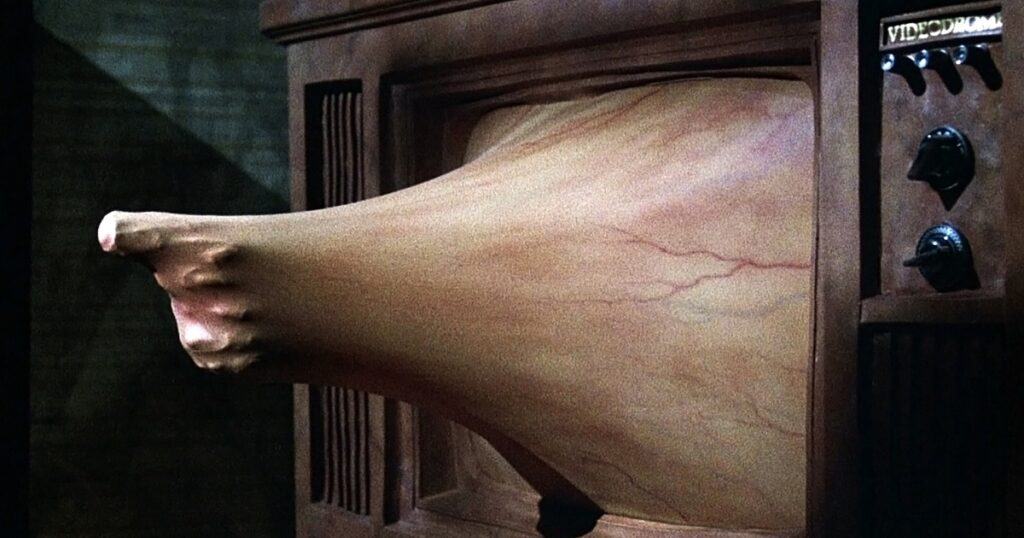

For the TV featured in the film, a real-life TeleRANGER model was used. According to Baker, the model was chosen because it was large enough to house the mechanical effects inside the physical apparatus. The SFX team built several models during production in order to test various FX methods, with Baker leading the experimental charge to push the envelope in ways for the technology to match the ambition of Cronenberg’s screenplay. According to Baker in a Criterion interview:

“I knew we would need a flexible material. And we tested it with a weather balloon first, stretching it over a flame the size of a TV screen and pushed a hand through it to see how far it stretched.”

According to Michael Lennick, it was a laborious effort to get the TV prop just right, telling Criterion that:

“We were originally going to do it as a blue screen effect. We were looking up various types of material… blue gelatin was one substance that we were working with, in which the actor could literally dunk his head into this stuff.”

Luckily, before submerging James Woods in a vat of Jell-O, a more artful solution was created. Harkening back to low-fi technology featured in King Kong, Baker and Lennick came up with a way of creating the heaving TV screen by using a projector and sheet of Dental Dam layered with extremely reflective white paint. Dental Dam was used in the early Hollywood days as a means of rear projection, which Baker noted: “was a nice sensual thing that James Woods could caress and it would respond.” Cronenberg agreed, adding in the DVD commentary that the result of the FX “had a tactility you don’t get with computer imagery.”

As for the freaky “breathing screen” FX in the film, Baker told Den of Geek in 2012 that it was achieved by first using a film camera to record a TV screen playing a performance of Debby Harry. The footage was then rear-projected through a large airtight plexiglass chamber onto an inflatable rubber sheet inside the television. This allowed the TV to contract and expand as needed for the scene, which required the collaborative efforts of the physical, makeup, and video FX teams. “I knew we would need a flexible material,” Baker told Cinefantastique, adding, “we tested with a weather balloon first, stretching it over a frame the size of a TV screen, and pushed a hand through it to see how far it stretched, and then we rear-projected on it.”

Baker expounded to Den of Geek in 2012, saying:

“I got the script and it had all this crazy ass stuff in it. I was like, ‘how the hell am I going to do this,’” adding that Videodrome was “one of the strangest assignments I’ve ever had” in the Criterion making-of documentary.

Indeed, Baker’s typical puppeteering methods included employing pullable wires, cables, and pressure controls. However, the TeleRANGER TV was too large to perform such a technique. Instead, physical effects supervisor Frank Carere came up with the idea to rig a keyboard organ with an air valve compressor pump, allowing the TV to balloon, restrict, and eerily undulate as needed throughout the sequence when Carere pressed certain keys. “It was something that evolved,” says Carere in the DVD commentary, adding, “I was trying to figure out how to control the maximum number of switches with my hands and then would I need two people, three people or four people or more. There was a lot of tweaking but Rick seemed very happy with the results so we went ahead and every night after shooting for a good week or 10 days, I stayed late just to work on the keyboard, and ultimately it gave us the control that we needed.”

Interestingly enough, according to Baker, Carere even found a proficient pianist to play Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor on the keyboard while operating the device to make it pulsate the way it does during the key scene in which Renn whips the TV set. That’s some serious f*ckin’ orchestration!

The videotapes inserted into Renn’s slit stomach cavity during the movie were actually Betamax cassettes, which were chosen because VHS cassettes were too large to fit properly inside the abdominal puncture. Woods found the stomach slit effect physically uncomfortable and began running out of patience with it, once lamenting that “I am not an actor anymore. I’m just the bearer of the slit” after a long day of filming while attached to the apparatus. The stomach slit sequence required Woods to be placed inside a couch built around him with the physical apparatus glued onto his chest. Woods was apparently so irate that he vowed never to have anything glued onto him for a movie ever again. As a playful form of payback, while filming the scene in which Renn shoots cold vaporous gas from his Flesh Gun, Woods painted his hand with blue paint prior to a take and briefly convinced Cronenberg that his hand was frostbitten.

When designing Renn’s iconic Flesh Gun, Baker originally conceived the prop to feature eyes, a mouth, and a foreskin, which Cronenberg found “too graphic” and discarded before it was created. In terms of the visual representations of cancer caused by Renn’s Flesh Gun, several tests were used to achieve the effect. Baker initially considered using solvents to distort the facial appearances but opted against the method upon realizing his longtime mentor Dick Smith used the same technique on Spasms in 1977 and didn’t want to appear like a phony copycat. In the end, it was Baker’s idea to show the cancer tumors erupting out of Barry’s body, which required the FX crew to operate a dummy of Barry’s body from beneath the set. According to Baker in the Criterion DVD commentary, “the effect where Barry Convex is coming apart, we had people under the set with their hands in these hot melt vinyl cancer puppets that had to come up and we had guys that were (operating) the arms of it and somebody else working some other part of the head. I remember after we shot the Barry Convex body all of us coming back to the hotel completely covered in this fake blood, this Caro sort of blood that is sticky as hell, and our shirts are stuck to us and we got in our hair, you know, it looked like we had been in some horrible accident.”

As for the distorted visual FX that occurs when Renn whips the TV set, Michael Lennick created a device he called the “Videodromer” to achieve such. Lennick also wanted to use Renn’s Videodrome helmet to create disorienting “glitch” and “twitch” FX that were ultimately scrapped before filming due to time and money concerns.

One thing casual and die-hard fans of the film may not know is that three different endings were filmed for Videodrome. The one used in the final cut was suggested by Woods, which ends with Renn shooting himself on the derelict ship. However, according to Cronenber via Criterion, an epilogue was originally planned but never filmed. The post-film sequence would have taken place after Renn’s suicide, in which he, Bianca, and Nicki appear on the Videodrome set, where the two women are shown to have bizarre biotech sex organs protruding from their own stomach slits that resemble Renn’s. According to Cronenberg:

“After the suicide, [Max] ends up on the ‘Videodrome‘ set with Nicki, hugging and kissing and neat stuff like that. A happy ending? Well, it’s my version of a happy ending—boy meets girl on the ‘Videodrome’ set, with the clay wall maybe covered in blood, but I’m not sure. Freudian rebirth imagery, pure and simple.”

Cronenberg attributed the dismissal of the epilogue to his own atheist beliefs in the DVD commentary, likening Renn’s resurrection to a connection to the afterlife, something the director does not believe in.

With the Christmas Eve production deadline fast approaching, Cronenberg and his FX team had one final shot to complete, which turned out to be such a disgusting moment on the set that many of those involved in the making of Videodrome remains haunted by. To achieve the shot of human brains jutting from the TV screen at the end of the film, real-life sheep guts were shot out of an air cannon. According to Carere, he went to an abattoir conveniently located across the street and requested sheep guts, fully expecting to be turned away. When he was told to return with green garbage bags 20 minutes later, the FX crew had the materials needed for the shot. However, it took at least a week from the time the sheep guts were acquired and when the effect was shot. By the time it came to filming, the overwhelming stench of rotten sheep guts was so strong it immediately cleared the room. “So at the last minute, we gloved up,” says Carere, adding “we put a breakaway glass screen in, we loaded the guts into the air cannon, and the rest is history.”

Unfortunately, the effect did not work as intended on the first take, requiring the entire crew to toil for an additional six hours one of the last days of a tiresome schedule to get it right. After Carere cranked the valves, the air cannon was wider, and the effect worked like a charm on the second take, which is what is seen in the film. The production finished the shot in the early hours of the Christmas Eve deadline.

Once principal photography concluded, Cronenberg reassembled his crew for a week of pick-up shots in the spring of 1982 to capture footage they were unable to during production and shoot new footage to accommodate what was cut in the editing room. “It was cut together in a manner that made it more than what we had shot,” claims Carere. According to Location Manager David Coatsworth, “the phrase the sum of the whole is greater than the sum of its individual parts… it’s a movie that has really stood the test of time. It’s a classic. Anybody who’s seen it remembers it.”

Cronenberg’s longtime musical collaborator Howard Shore created the trippy soundscape for the film, which was meant to aurally represent the hallucinatory headspace that Renn and the other’s experience, starting with classic orchestration that slowly devolves into electronic synth sounds. Shore achieved the feat by composing the entire soundtrack for an orchestra before recording it in a Synclavier II digital synthesizer. The synth recording was then played along with a small string section, creating a haunting, otherworldly effect (per Cinefantastique).

All of the combined organic, practical, physical, and DYI special FX is one the main reasons why Videodrome retains such an original aesthetic and no doubt one of the chief reasons why the film has attained all-time beloved cult status over the past 40 years.

Unfortunately, for all the excellent work that went into the making of Videodrome, the film took a financial drubbing at the box office when it was released in theaters on February 4, 1983. With a final production budget of $5.9 million, the film failed to earn even half of its money back, netting a total of $2.1 in international ticket sales. The film was declared a box office bomb but luckily enough for Cronenberg, his adaptation of Stephen King’s The Dead Zone released the same year became a big enough hit to allow the director to soar to new heights with his follow-up film, The Fly, which nearly tripled its budget at the box office and solidified Cronenberg as a bona fide filmmaker in the eyes of Hollywood.

Yet aside from the financial failure of Videodrome, the film drew endless praise from critics and filmgoers for its outlandish vision and original fusion of body horror and lofty science fiction tropes that would become synonymous with Cronenberg’s filmmaking style.

Interestingly enough, despite Videodrome not being released on VHS and DVD until the late 1990s, the film’s popular word of mouth became so strong that it won a slew of awards in 1984, including 8 Genie Award nominations and a win for Cronenberg’s Best Achievement in Directing, which he shared with Bob Clark for his stellar work in the classic holiday film A Christmas Story. Of course, Clark also helmed Black Christmas a decade prior, giving the two directors an inextricable horror link for their careers. The grand irony is that while A Christmas Story was a box office hit at the time and has since become an annual TV mainstay, Videodrome overcame its poor box office performance to become nearly as popular in horror/sci-fi circles. In 2010, Videodrome was listed by the Toronto International Film Festival as the 89th most-essential film in history, cementing the film as an all-time great despite its financial failings at the time of its release.

And that’s essentially What The F*ck Happened to Videodrome. The film entered production without a completed screenplay, took two months to film under a tightly mandated deadline by a Canadian government that funded the project, featured an incredibly inventive time for a young team of make-up, practical, and video effects collaborators working under the supervision of the great Rick Baker, leading to some of the inspired and innovative Special FX work in the 1980s that, despite its commercial hiccups at the time, has remained into the collective conscious of pop culture 40 years later as one of the most outlandishly original, sexily surreal, nastily nightmarish, deeply disturbing yet oddly arousing cinematic curios ever committed to celluloid. Sometimes a movie becomes a cult classic for all the wrong reasons. However, Videodrome proves that the merits of high-quality work will inevitably find its audience and become celebrated for what it continues to give to audiences generation after generation. Long Live The New Flesh, indeed!

Originally published at https://www.joblo.com/wtf-happened-to-videodrome/